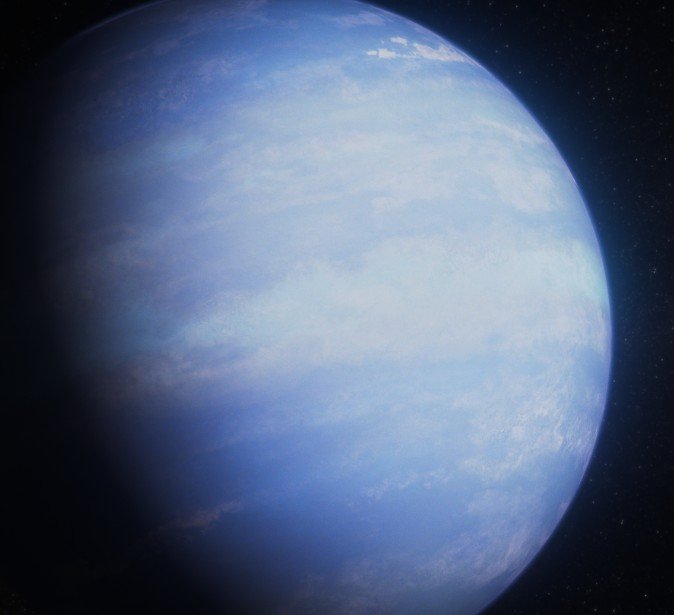

Astronomers using the James Webb Space Telescope have detected massive clouds of helium leaking from exoplanet WASP-107b, uncovering dramatic atmospheric loss that could explain how ultra-puffy planets evolve over time.

A Planet Losing Its Atmosphere at a Remarkable Scale

WASP-107b sits roughly 210 light-years from Earth.

It circles its parent star so closely that its upper atmosphere is constantly blasted by radiation.

This bombardment appears to be stripping the planet’s gases at a staggering rate.

Scientists observed a helium envelope stretching nearly ten times the planet’s radius.

One-line pause: that’s an atmosphere so swollen it barely holds together.

The gas isn’t just drifting upward.

It’s escaping in twin streams—one flowing ahead of the planet along its orbit, and another trailing behind like a long, thin comet tail.

Astronomers say the discovery gives fresh clarity to how “super-puff” planets lose mass.

These are worlds so light and airy that they appear almost cotton-like in density.

What the Webb Telescope Revealed About WASP-107b

The James Webb Space Telescope’s infrared sensitivity made this detection possible.

Earlier instruments hinted at helium around WASP-107b, but nothing this dramatic.

Webb captured clear signatures that the planet’s upper atmosphere isn’t just extended—it’s hemorrhaging.

The helium sits in what scientists call an exosphere, the outermost shell of gas.

As the star heats the atmosphere, helium atoms gain enough energy to escape gravity’s pull.

The process is similar to watching steam rise from boiling water, but on a cosmic scale.

A quick one-sentence breath fits here: WASP-107b is literally shedding part of itself into space.

Researchers say this runaway escape could ultimately shrink the planet over millions of years.

That shifting profile may explain why similar super-puff planets evolve into smaller, denser worlds.

Here’s one bullet-point takeaway that captures the heart of the finding:

-

Webb’s data shows helium drifting nearly 100,000 kilometers from the planet, forming long plumes shaped by stellar winds.

It’s a scale almost impossible to imagine until you see the simulations.

How Super-Puff Planets Lose Their Air

WASP-107b is known for its unusual structure.

It’s roughly the size of Jupiter but far less massive.

That means the atmosphere sits loosely—almost like a bubble around a balloon.

So even a modest push from stellar energy can send gas streaming outward.

Because the planet orbits so close to its star, its outer layers heat up dramatically.

This creates what scientists call “hydrodynamic escape,” where gas flows away in bulk rather than atom by atom.

One-line pause: the planet is basically evaporating.

Researchers think this escape might explain why some super-puffs vanish from telescope surveys after a few billion years.

They slim down into smaller, rocky cores or Neptune-like remnants.

Observing WASP-107b gives a rare view of that transformation in real time.

It’s like catching a photo of a melting ice sculpture just before it collapses.

The Shape of the Helium Envelope Tells a Bigger Story

The helium cloud forms a huge teardrop shape around WASP-107b.

Its front and back ends stretch along the orbital path, molded by the star’s streaming particles.

This alignment tells scientists that stellar winds play a major role in shaping the escape.

The gas doesn’t just float upward—it gets pulled and stretched.

A small one-sentence break here: the planet’s orbit acts like a canvas for the helium to smear across.

Simulations show the helium plume changing size as the planet moves through different wind intensities.

Some days, the cloud appears denser; other days, it thins out like smoke.

This variability helps astronomers track how energetic the star is.

A more active star means faster escape.

Webb’s data suggests WASP-107b might be losing its atmosphere at a rate high enough to strip much of its envelope within a few billion years.

That’s a blink on cosmic timelines but long enough for astronomers to watch changes accumulate.

What This Means for Exoplanet Evolution Research

The helium detections give a new benchmark for studying close-in gas giants.

For years, scientists knew many hot exoplanets lose mass—but the scale was uncertain.

Seeing helium stretch to ten times the planet’s radius gives researchers a more precise way to measure atmospheric escape.

It shifts theoretical models significantly.

A quick one-liner: planets like WASP-107b may carve an evolutionary path different from classical gas giants.

If atmospheric depletion continues, the lightweight super-puff could eventually resemble planets closer to Neptune in size.

Or, in some cases, leave behind a bare rocky core.

These insights also reshape expectations for exoplanet demographics.

Many close-in planets discovered by previous missions may have looked different billions of years ago.

Here’s a simple table that summarizes the major atmospheric features found on WASP-107b:

| Feature | Observation |

|---|---|

| Helium Envelope | Extends ~10× planetary radius |

| Escape Pattern | Streams ahead and behind orbit |

| Escape Driver | Stellar heating + wind shaping |

| Estimated Effect | Long-term atmospheric loss |

| Detection Tool | James Webb Space Telescope |

This table shows how each clue fits into the bigger picture of mass loss.

Why WASP-107b Keeps Fascinating Scientists

Super-puff planets are rare.

They look like gas giants but weigh a fraction of what you’d expect.

That alone makes them strange.

But when you add atmospheric escape the size of a small star system, they become irresistible targets for observation.

Astronomers say WASP-107b is among the best laboratories for studying how planets evolve under extreme conditions.

It sits close enough to its star, and remains large enough, to make these processes visible.

One-sentence pause: it’s the kind of planet that teaches you more by breaking the rules.

Webb’s continued monitoring may reveal how quickly the helium plume changes over time.

New results could also refine estimates of how long the atmosphere will last.

For now, the planet remains an extraordinary example of how dynamic exoplanets can be—losing gas, shifting shapes and slowly redefining themselves.