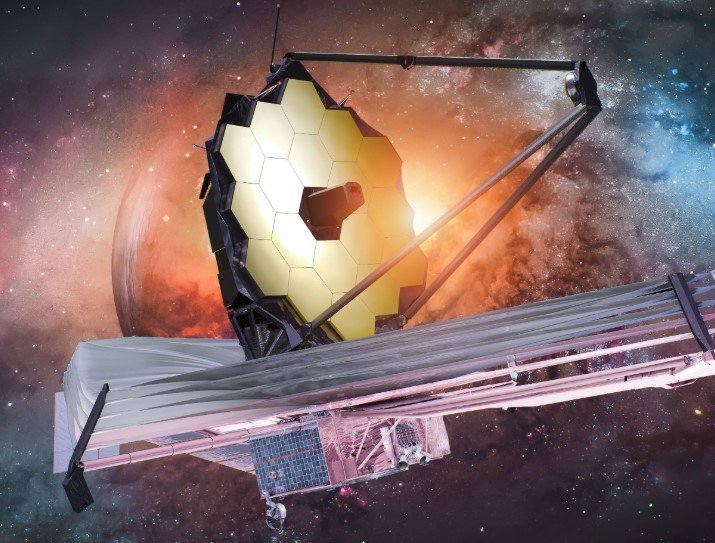

The James Webb Space Telescope has been hailed as humanity’s sharpest eye in the sky, but the big question lingers: could it actually find another Earth? Scientists say the answer isn’t simple—and it’s sparking a wave of excitement, debate, and patience-testing in equal measure.

What “Earth 2.0” Really Means

When astronomers talk about “Earth 2.0,” they don’t just mean a rock floating in the habitable zone. They’re talking about a place that feels like home—a world with oceans, continents, clouds, and the invisible chemistry that allows life to breathe.

That definition immediately narrows the search. Thousands of exoplanets have been discovered since the mid-1990s. But a true “second Earth”? That bar is set much higher.

Some scientists compare the hunt to standing on a mountain ridge, looking at countless peaks, and trying to find the one that hides a village just like yours. You know the signs, but the distance blurs the details.

How Webb Hunts for Clues

The James Webb Telescope, sitting a million miles from Earth, doesn’t snap postcard-like images of alien beaches. Instead, it looks at starlight. When a planet passes in front of its star, Webb measures the way light filters through its atmosphere.

This technique—transit spectroscopy—works like holding a glass of colored water up to the sun. Depending on what’s in the glass, the light changes. On planets, that means gases like oxygen, methane, or water vapor.

Even tiny shifts in color tell stories. Webb’s infrared instruments are sensitive enough to pick up those changes, giving scientists a fingerprint of what a distant atmosphere might contain.

And while that sounds abstract, it’s the closest thing we’ve ever had to sniffing the air of another world.

The Most Intriguing Targets

Astronomers aren’t shooting in the dark. Some stars already stand out as promising. The TRAPPIST-1 system, just 40 light-years away, has seven planets circling a cool red star. At least three sit in the zone where water could exist as a liquid.

For scientists, that’s basically a cosmic jackpot. Webb is now scrutinizing these worlds, one by one, looking for steady atmospheres that could shield water and life.

Beyond TRAPPIST-1, there are others:

-

Kepler-452b, sometimes dubbed “Earth’s cousin,” though it’s much bigger.

-

Proxima Centauri b, orbiting the star closest to our Sun, though it faces fierce stellar flares.

-

LHS 1140 b, a rocky super-Earth in the habitable zone, considered a strong candidate.

Each planet has quirks. Some might be too hot, others too frozen. But with every data set Webb collects, the picture sharpens, and the odds shift.

Why It’s So Hard

Finding Earth 2.0 isn’t like flipping through a catalog. The universe is unimaginably vast, and even nearby exoplanets are so far that direct imaging is almost impossible right now.

Oceans, coastlines, forests—those are far beyond Webb’s reach. What it can offer are atmospheric fingerprints, the chemical whispers that suggest something familiar.

And even those whispers are faint. A single measurement might not be enough. Researchers need repeated observations, sometimes spread over months or years, to be sure they’re not seeing noise.

As one astrophysicist put it recently, “This is a marathon, not a sprint. Webb gives us the starting gun.”

The Road Ahead

Webb’s job might be less about discovery and more about pointing the way. If it identifies planets with atmospheres rich in water vapor or oxygen, future missions can follow up with sharper tools.

NASA is already planning the Habitable Worlds Observatory, set to launch in the 2030s. Unlike Webb, it’s being built to directly photograph Earth-like planets, not just study their atmospheres. The hope is to catch an actual pale blue dot orbiting another star.

Other projects, like ESA’s Ariel mission or the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, will add more pieces to the puzzle. They’ll expand the list of candidates and refine the techniques, building a ladder that might one day reach Earth 2.0.

Here’s a quick snapshot of what’s on the horizon:

| Mission | Launch Year | Goal |

|---|---|---|

| JWST | 2021 (active) | Atmospheric analysis of exoplanets |

| Roman Space Telescope | Mid-2027 | Wide exoplanet survey |

| Ariel (ESA) | 2029 | Study atmospheres of 1,000+ exoplanets |

| Habitable Worlds Observatory | 2030s | Direct imaging of Earth-like planets |

For now, Webb is our best chance. It may not deliver a postcard of a twin Earth. But it could point to the most likely candidates—planets worth the long wait and investment.

And that, for many astronomers, is enough to keep hope alive. Because if even one such planet is confirmed, it would change everything we thought we knew about life in the universe.