A copper plate dug up in Andhra Pradesh has cracked open a time capsule from 1456, revealing what is likely India’s oldest written reference to Halley’s Comet — and the dread it inspired.

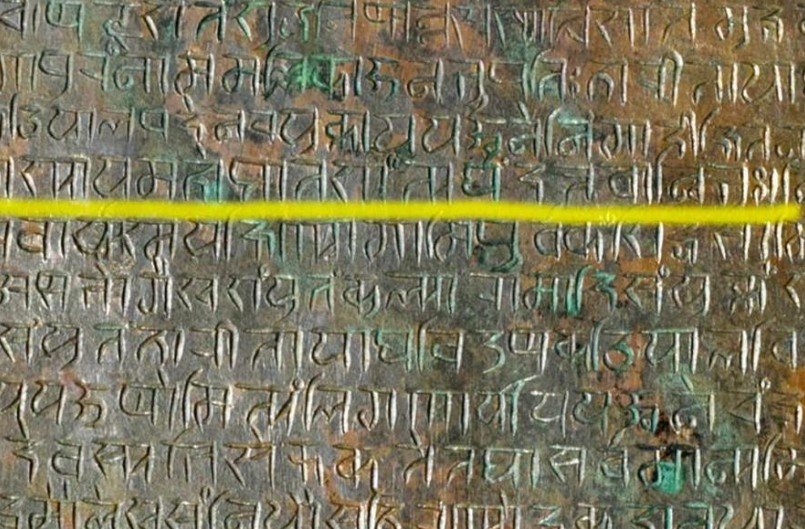

A weathered copper plate etched in Sanskrit has just thrown open a new window into medieval India’s night sky. Found in Srisailam, Andhra Pradesh, and dated to 1456 CE, the inscription records the sighting of a blazing comet — now believed to be Halley’s — and the ominous mood it cast over the Vijayanagara court.

For historians and astronomers alike, this isn’t just another royal grant document. It’s the earliest known epigraphical mention of Halley’s Comet in India. And it’s a rare example of how the cosmos directly impacted decisions on Earth — in this case, a royal land donation.

A Royal Panic Written in Metal

Unlike palm-leaf manuscripts that decay in decades, copper plates last centuries. And this one — penned in Nāgari script and composed in Sanskrit — has survived long enough to shock modern scholars.

It marks a grant from Vijayanagara king Mallikārjuna to a Vedic scholar named Liṁgaṇārya, dated precisely to Āshāḍha ba.11, Śaka 1378, which converts to July 1456.

That date matters. It aligns with one of Halley’s documented returns — the same year when Chinese, Egyptian, and even European records reported a terrifyingly bright comet in the sky.

And in India? Apparently, the sky falling meant it was time to give away land.

More Than Just a Star With a Tail

What’s striking is the language used. The plate refers to “a serpent-like fire in the sky” and “flaming swords” — vivid metaphors describing the comet’s tail and accompanying meteor showers. The comet, it says, caused “turmoil among the stars” and “deep unrest in the court.”

Not bad for medieval observational astronomy.

Experts believe this shows a working awareness — if not a scientific understanding — of celestial cycles. Director of Epigraphy at the ASI, K. Munirathnam, told South First that they confirmed the date with NASA’s own Halley’s Comet data. While NASA stopped short of certifying the link, the orbital timing lines up neatly.

Global Panic, Local Impact

India wasn’t alone in freaking out.

-

In Egypt, astrologers warned of dynastic collapse.

-

In China, it was seen as a bad omen for the emperor.

-

In Kashmir, Sanskrit scholar Śrīvara mentioned the comet as a sign of political upheaval.

Back in Srisailam, though, King Mallikārjuna seemed to act on instinct: do something generous, and maybe the sky gods would calm down.

Here’s a breakdown of global records from 1456:

| Region | Reaction to Halley’s Comet in 1456 |

|---|---|

| China | Detailed meteorological logs; seen as imperial warning |

| Egypt | Astrological predictions tied to plague and instability |

| Europe | Papal order to pray against the comet’s evil effects |

| Kashmir | Śrīvara links it to political shifts |

| Vijayanagara | Royal land grant to calm cosmic unrest |

The Cultural Fear Factor

Comets weren’t just shooting stars to ancient observers — they were omens, pure and simple. People feared them like modern folks might fear nuclear war or market crashes.

Karen Aplin, physicist at the University of Bristol (who was not involved in this specific study), has written about how cosmic phenomena shaped ancient policy and belief. “Comets, because they appear suddenly and then vanish, often became stand-ins for political uncertainty,” she once told Sky & Telescope.

This copper plate fits that pattern like a glove.

Linguistic and Archaeological Crossroads

What makes this discovery even more compelling is its location and script. Srisailam isn’t some obscure village. It’s a major Shaivite pilgrimage site and a cultural hub during the Vijayanagara Empire.

And Nāgari — a precursor to modern Devanagari — was the elite script of scholars and priests. So this wasn’t village folklore. It was high literature, etched in metal, meant to last forever.

The grant itself was to Liṁgaṇārya of Kaḍiyalapura, now Kadapa district. His family had apparently performed elaborate Vedic rituals to appease the “celestial fire-serpent.” The plate suggests their intervention was successful — or at least politically convenient.

A New Lens on Medieval Science

The find adds to growing evidence that India had a more nuanced astronomical tradition than it often gets credit for.

Sure, we had Aryabhata and Bhaskara centuries earlier. But this inscription proves that by the 15th century, cosmic events still mattered — not just to scholars, but to rulers and commoners alike.

And it wasn’t just about tracking the skies. It was about reacting to them.

-

Fear of celestial chaos wasn’t superstition — it drove real decisions.

-

Land grants, rituals, political resets — all tied to what was above.

-

Epigraphy shows how astronomy and anxiety often went hand in hand.

One Inscription, Many Questions

So what happens now?

The ASI plans to digitize the plate and collaborate with Sanskrit scholars to create a full critical edition. There’s already talk of looping in NASA historians for cross-referencing global records of Halley’s 1456 flyby.

And yes, more plates from the Srisailam cache are being decoded. Who knows what else might be in there — maybe other cosmic events, eclipses, or even meteor showers tied to political changes.

For now, this copper plate is more than just a pretty artifact. It’s a blinking arrow from the past, reminding us that the sky has always mattered — not just in science, but in fear, faith, and how we try to make sense of the chaos around us.