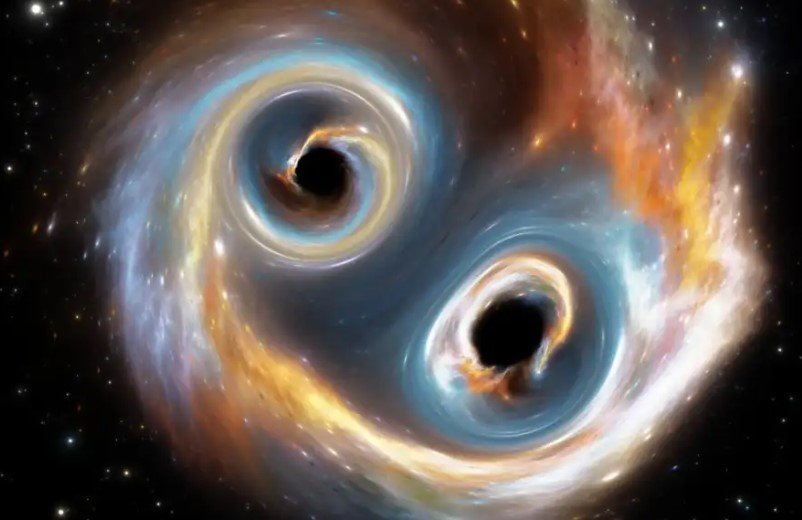

Scientists at the LIGO Virgo KAGRA Collaboration announced the detection of GW231123, the most massive black hole merger observed so far, on November 23, 2023. This event, revealed in July 2025, involved two huge black holes colliding to form a new one about 225 times the mass of our sun, raising big questions about how stars and black holes form.

What Happened in the Merger

The gravitational wave signal came from a distant corner of the universe, about 2.2 billion light years away. It lasted just a tenth of a second, but packed enough power to shake our understanding of space.

Experts say the two black holes had masses around 137 and 103 times that of the sun. When they smashed together, they released energy equal to several suns turning into pure waves. This made the final black hole a giant in the intermediate mass range, between stellar and supermassive types.

Detection relied on LIGO’s Hanford and Livingston sites in the US, which picked up the signal clearly. The network’s signal to noise ratio hit 20.7, confirming it was no fluke.

This find builds on past detections, like GW190521 from 2020, which was the previous record holder at 142 solar masses. Now, GW231123 tops that, showing these events might be more common than thought.

Why It Challenges Standard Theories

Current ideas about star life cycles say black holes form from dying stars, but not all sizes are possible. A key rule predicts a gap where no black holes should exist from single stars.

This gap comes from pair instability, a process in very massive stars. When these stars run low on fuel, their cores heat up and create pairs of particles that drop pressure inside. The star then explodes fully, leaving no black hole behind.

The theory sets this gap between 50 and 130 solar masses. But GW231123’s black holes sit right in that zone, with one at 130 and the other at 101 solar masses.

- Stars below 50 solar masses can collapse into black holes after supernovas.

- Between 50 and 130, pair instability blows them apart completely.

- Above 130, they might form black holes again, but that’s rare.

This merger suggests other ways black holes could form or grow, like from earlier mergers or in dense star clusters.

Details of the Black Holes Involved

Both black holes spun fast, with speeds measured at 0.9 and 0.8 on a scale where 1 is the max. High spins hint they might have come from previous mergers, not just single stars.

The event’s data shows the merger released energy in gravitational waves, turning about 15 solar masses into ripples that traveled across space.

Here’s a quick comparison of key black hole mergers:

| Event | Date Detected | Primary Mass (Solar) | Secondary Mass (Solar) | Final Mass (Solar) | Distance (Billion Light Years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GW231123 | Nov 2023 | 137 | 103 | 225 | 2.2 |

| GW190521 | May 2019 | 85 | 66 | 142 | 5.3 |

| GW150914 | Sep 2015 | 36 | 29 | 62 | 1.3 |

This table highlights how GW231123 stands out in size and what it means for records.

Astronomers note the spins and masses don’t fit easy with standard star evolution. Instead, they point to dynamic environments, like globular clusters, where black holes can pair up and merge multiple times.

Broader Impacts on Astrophysics

This discovery opens doors to rethink black hole origins. If black holes can form in the mass gap, it might mean more intermediate ones exist, bridging stellar and supermassive types.

It ties into recent events, like GW250114 in 2025, which confirmed Hawking’s area theorem during a merger. That find showed black hole surfaces grow or stay the same, matching predictions from the 1970s.

Experts believe future runs of LIGO and similar detectors will spot more such events. Upgrades planned for 2026 could boost sensitivity, helping map the black hole population.

On a practical side, these waves give a new way to test gravity theories. They confirm Einstein’s general relativity holds up, even in extreme cases.

What It Means for Future Research

The challenge to the pair instability mass gap pushes scientists to explore new models. Some suggest low metal stars or rapid accretion could allow black holes in that range.

Indian researchers in the LVK group played a key role, analyzing data and modeling waveforms. Their work helps global efforts to understand cosmic evolution.

As detectors improve, we might see mergers involving neutron stars or other odd pairs. This could reveal how the universe builds its biggest structures.

Share your thoughts on this cosmic shake up in the comments below, and pass the article along to fellow space fans. What do you think it means for our view of the stars?