The search for life beyond Earth has shifted from philosophy to data. With thousands of known exoplanets and powerful new telescopes scanning their skies, astronomers are now reading alien atmospheres for clues that biology might be at work somewhere else.

A census of distant worlds changes the question

For most of human history, the idea of planets around other stars sat somewhere between guesswork and faith. That changed fast. In just three decades, astronomers have confirmed more than 6,000 exoplanets orbiting stars beyond our Sun, a tally that grows almost monthly.

This flood of discoveries has altered the tone of the debate. The question is no longer whether planets exist elsewhere. They do. Plenty of them.

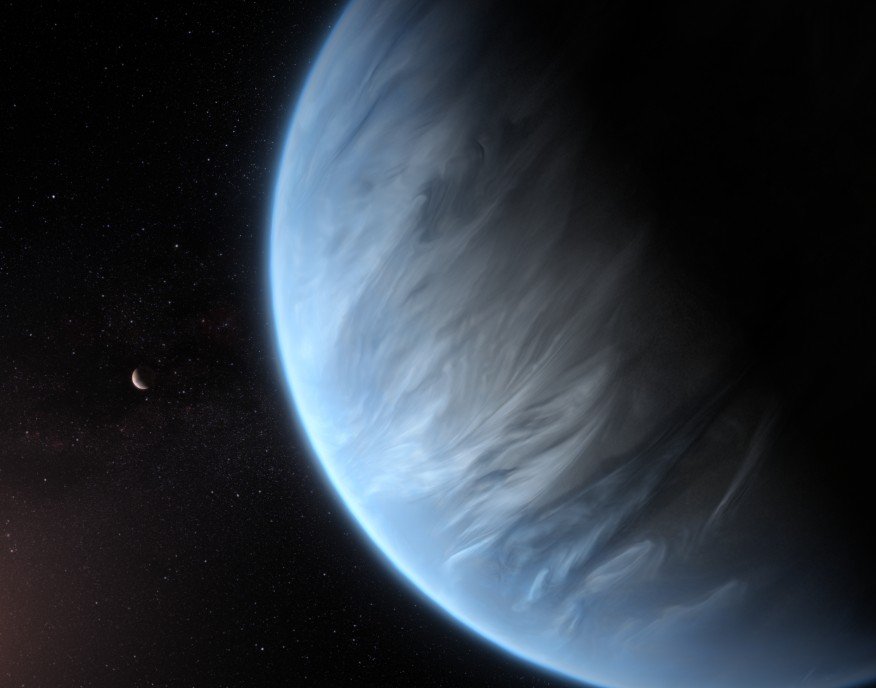

Some are blisteringly hot gas giants hugging their stars. Others are frozen worlds drifting in dim orbits. A smaller, far more interesting group sits in what scientists call the habitable zone, where temperatures could allow liquid water.

And water, as far as we know, is kind of a big deal.

Missions like Kepler Space Telescope and its successor, TESS, helped build this planetary census. They didn’t look for life directly. Instead, they found where to look next.

Reading alien air for hints of biology

Astronomers can’t visit these planets. Not even close. Most are dozens or hundreds of light-years away. So they do the next best thing: they study the light passing through a planet’s atmosphere.

When a planet crosses in front of its star, a tiny fraction of starlight filters through the gases surrounding that world. Different gases leave different fingerprints in that light.

Oxygen, methane, carbon dioxide, water vapour. These are the big ones.

On Earth, some of these gases are closely tied to life. Oxygen, for instance, is highly reactive. Without plants and microbes constantly replenishing it, Earth’s oxygen-rich atmosphere would fade away.

That imbalance is what excites scientists.

They look for combinations of gases that shouldn’t coexist for long unless something is actively producing them. It’s less about spotting a single molecule and more about catching a chemical argument in progress.

Still, caution rules the day. Volcanoes, stellar radiation, and exotic chemistry can sometimes mimic life-like signals. False positives are a real worry.

The James Webb moment arrives

This is where James Webb Space Telescope enters the story.

Unlike earlier space telescopes, Webb was built with atmospheric analysis in mind. Its infrared instruments can tease out faint chemical signatures from exoplanets that were previously out of reach.

In its first years of operation, Webb has already detected water vapour, carbon dioxide, and methane in several alien atmospheres. None of these discoveries prove life exists elsewhere. But they show the method works.

One planetary system keeps popping up in these discussions: TRAPPIST-1.

This small, cool star hosts seven Earth-sized planets, several in or near the habitable zone. Webb’s observations are beginning to place limits on what kinds of atmospheres these worlds might have.

Some appear airless. Others may still hold thick blankets of gas.

It’s slow work. Careful work. And yes, a bit nerve-wracking.

What counts as a sign of life, anyway?

Even if Webb or a future telescope spots an intriguing mix of gases, the argument won’t end there. Scientists are painfully aware of how easily excitement can run ahead of evidence.

So they’ve drawn up a rough hierarchy of signals, from suggestive to compelling.

Some atmospheric clues are more persuasive than others:

-

Simultaneous presence of oxygen and methane far from chemical balance

-

Seasonal changes in gas concentrations

-

Detection of complex organic molecules unlikely to form by chance

None of these alone would settle the question. Together, they might start a serious conversation.

Still, extraordinary claims demand extraordinary scrutiny. Every potential biosignature gets tested against non-biological explanations, again and again.

It can feel frustratingly slow. But that’s science doing its job.

Past telescopes laid the groundwork

Webb gets much of the spotlight now, but it stands on the shoulders of earlier observatories.

The Hubble Space Telescope, launched in 1990, was among the first to probe exoplanet atmospheres. Its instruments detected sodium, water vapour, and clouds on distant worlds, hinting that atmospheric studies were possible at all.

Ground-based telescopes joined in too, using clever tricks to separate faint planetary signals from overwhelming starlight.

Each generation improved the playbook.

By the time Webb launched, astronomers knew what questions to ask and where the pitfalls lay. That experience matters more than shiny hardware alone.

How close are we to an answer?

This is the part people really want to know. Are we years away from proof of life elsewhere, or centuries?

The honest answer sits somewhere in between.

Within the next decade, astronomers expect to identify a shortlist of nearby rocky planets with atmospheres that look, well, interesting. Not proof. But interesting enough to argue over in journals and conferences.

Future missions are already on the drawing board. Concepts like NASA’s Habitable Worlds Observatory aim to directly image Earth-like planets and analyse their light in even greater detail.

Here’s a snapshot of how current and planned telescopes compare:

| Telescope | Primary Role | Life Detection Capability |

|---|---|---|

| Hubble | UV/visible astronomy | Limited atmospheric hints |

| James Webb | Infrared spectroscopy | Detailed gas analysis |

| Habitable Worlds Observatory (planned) | Direct imaging | Strong biosignature potential |

None of this guarantees a discovery. The universe may be quiet. Or life may be rare, fleeting, or simply harder to spot than we expect.

But for the first time, the tools match the ambition.

A question that refuses to fade

There’s something deeply human about this search. It’s not just about microbes or chemistry. It’s about context.

If life exists elsewhere, even simple life, it would suggest biology emerges readily when conditions allow. Earth would be one example among many.

If we find nothing, despite decades of careful searching, that silence would speak too. It would make our planet feel even more fragile, more unusual.

Either answer reshapes how we see ourselves.

For now, astronomers keep staring at tiny dips in starlight, pulling meaning from fractions of a percent. It sounds absurd when you say it out loud. Yet here we are.