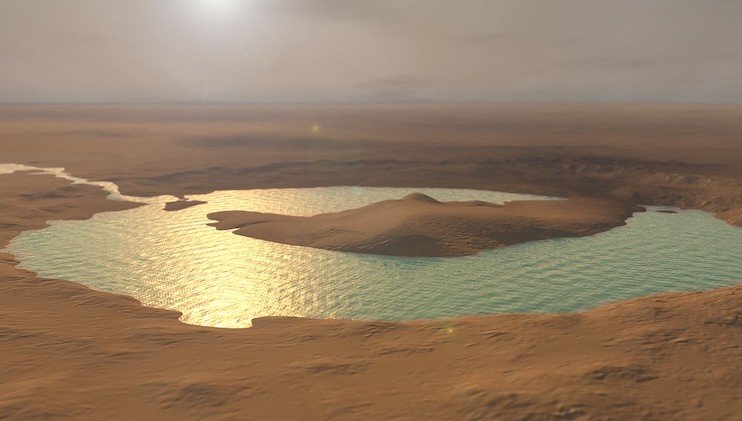

Scientists have completed the first comprehensive mapping of ancient river networks on Mars, uncovering large drainage basins that reveal how water once moved across the planet’s surface and reshaped its climate story.

A Planet Carved by Water, Not Wind Alone

For years, researchers could only piece together fragments of Mars’ watery past.

Now they’ve stitched together a clearer picture.

A new study identified 19 clusters of valleys, channels, lakebeds and sediments scattered across the Martian crust.

Sixteen of them connect into sweeping drainage basins—vast networks strikingly similar to Earth’s river systems.

That discovery alone shifts the way scientists talk about early Mars.

It wasn’t a place dotted with isolated streams; it may have been a world filled with connected water pathways.

A small one-line pause here: Mars once had organized water circulation, not random trickles.

These drainage systems, the researchers noted, handled large volumes of eroded material despite covering relatively small surface areas.

That suggests the rivers carried strong, persistent flows.

And suddenly the old image of Mars as a cold, dry rock seems too simple.

How Scientists Mapped a Dead Planet’s Rivers

Researchers used high-resolution imagery from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, the European Space Agency’s Mars Express, and terrain models constructed from laser altimetry.

The Idaeus Fossae region, with its tangled valleys, served as a key reference point.

Shadows inside channels, fan-shaped sediment deposits, and slopes indicated water movement patterns millions—possibly billions—of years ago.

Each feature had to be verified against volcanic or tectonic explanations.

In many regions, scientists found that valleys linked into long, branching systems.

Those systems led to deeper basins that behaved like ancient lakes or inland seas.

Here’s one bullet-point insight that captures the significance:

-

Mars may have once supported connected, continent-scale drainage routes similar to those on Earth.

That notion changes how researchers think about ancient Martian rainfall, snowmelt and groundwater.

A short sentence fits here: climate models now have to account for more water, lasting longer.

The team then reconstructed how these channels joined together, forming immense hydrological networks shaped by erosion and changing climate cycles.

The Climate Clues Hidden Inside Martian Valleys

The structure of these valley networks offers a window into Mars’ forgotten climate.

The shape of channels suggests long-term surface runoff rather than short-lived flash floods.

Wide, shallow valleys imply repeated flow.

Deep canyons imply stronger and more sustained erosion.

Some basins appear to have overflowed, draining into adjacent systems during wetter periods.

Others trapped water, forming enclosed lakes that gradually evaporated.

There’s a natural one-line pause here: water doesn’t carve landscapes like this unless it sticks around.

The presence of sediment fans indicates cycles of flow and drying.

Those cycles match evidence of ice transitions found in other regions.

A simple table helps outline what researchers found across the clusters:

| Feature Type | What It Suggests |

|---|---|

| Wide valleys | Continuous surface runoff |

| Deep channels | Strong, long-lasting river erosion |

| Basin overflows | Periods of higher water volume |

| Fan deposits | Seasonal or episodic flow cycles |

| Linked networks | Large-scale water circulation |

These clues collectively point to a Mars that experienced sustained hydrological activity—far more complex than earlier models predicted.

What the New Map Means for Habitability

Water is central to every discussion about life beyond Earth.

So this discovery immediately touches on habitability questions.

If rivers once moved across large parts of Mars, then stable climates may have existed for long stretches.

That means temperatures remained above freezing in key regions for long enough to support microbial ecosystems.

A one-sentence paragraph here: connected rivers often mean connected habitats.

Sediments within these basins could still contain chemical markers of ancient life.

NASA’s Curiosity rover found such hints in Gale Crater years ago, but this new study broadens the search area dramatically.

If these river systems were once as widespread as the data suggests, then potential habitats might not be rare—they might be common across the ancient planet.

Scientists say the next stage is correlating these drainage networks with mineral deposits like clays, sulfates and carbonates.

Those minerals store information about pH levels, salinity and atmospheric conditions.

Understanding how climate changed across the entire planet could deepen our sense of when Mars lost its rivers—and why.

A New Framework for Reading Mars’ Geological Past

Until now, most studies focused on small, isolated features.

But this mapping project treats Mars more like Earth: a system of interconnected landscapes.

It’s surprisingly emotional for some researchers who spent decades studying scattered valleys that seemed unrelated.

Suddenly, those lonely features fit into a planetary mosaic.

One-sentence pause: it feels like finding missing puzzle pieces buried for ages.

This new framework also helps scientists explain the planet’s dramatic climate shift.

Once the atmosphere thinned and temperatures fell, water retreated underground or froze.

What remains today is a ghost map of what once flowed freely.

The drainage clusters and basin connections allow geologists to approximate how much water Mars once held—and the answers point to huge volumes, potentially rivaling small terrestrial oceans in certain epochs.

Even if only a portion of that water covered the surface, it was enough to carve canyons, shape valleys, fill crater lakes, and transport sediment over vast distances.

All from a planet we now see as dry and quiet.

Why This Study Changes More Than Maps

For scientists working on missions like NASA’s Perseverance rover or the upcoming Mars Ice Mapper, these findings reshape exploration priorities.

Valley clusters could become new targets for sampling.

They also affect landing site decisions for future missions.

Places once dismissed as unremarkable may now be prime regions for studying ancient climates.

A short one-liner: the map turns old “dead zones” into potential scientific gold mines.

These results ripple outward to climate studies too.

Understanding Mars’ hydrology helps researchers test models of atmospheric loss, radiation exposure and planetary evolution.

And there’s the public impact.

Images of Mars already fascinate people worldwide, but photos of ancient river systems—still visible after millions of years—give a sense of a living past.

The idea that a dry planet once buzzed with flowing water makes Mars feel strangely familiar.

Almost Earth-like in its youth.