Early on March 19, a SpaceX capsule splashed down in the Gulf of Mexico, carrying astronauts Sunita Williams, Barry Wilmore, Aleksandr Gorbunov, and Nick Hague back to Earth. For Williams and Wilmore, the return marked the end of a grueling nine-month mission aboard the International Space Station (ISS). Now, they face an equally demanding challenge: regaining their strength and adapting to life under gravity.

Life After Microgravity: The Body’s Reset Button

Spending months in microgravity takes a toll on the human body. Without Earth’s pull, fluids shift upward, muscles weaken, and bones lose density. Williams and Wilmore aren’t just astronauts — they’re now subjects of a full-body reboot.

NASA has a carefully structured regimen waiting for them. It starts with medical evaluations, tracking everything from heart rate to balance control. Muscle mass and bone density loss are among the top concerns. While on the ISS, astronauts exercise two hours a day to slow this decline. But even that isn’t enough to prevent it entirely.

One major challenge? The vestibular system — responsible for balance — goes haywire after months in space. Astronauts often report feeling like they’re still floating, even when they’re firmly on Earth. Williams and Wilmore will work with specialists to retrain their inner ears and stabilize their sense of direction.

Why Physical Therapy Isn’t Optional

Physical therapy isn’t a luxury — it’s a necessity. Without it, astronauts risk long-term issues, from muscle atrophy to weakened bones that could fracture easily.

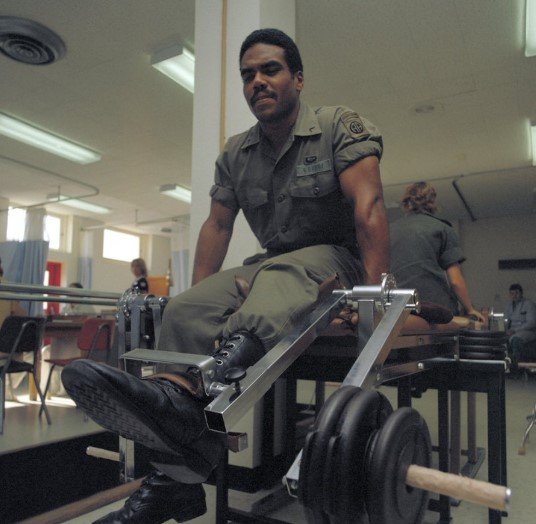

The rehab plan includes:

- Strength training to rebuild lost muscle mass.

- Cardio workouts to restore heart and lung endurance.

- Balance exercises to reset the vestibular system.

- Stretching routines to counteract stiffness from fluid shifts.

Williams and Wilmore will also undergo nutrition assessments. Space food is balanced to prevent deficiencies, but the body processes nutrients differently in space. Now back on Earth, their metabolisms need monitoring to ensure they absorb everything properly.

Psychological Impact: More Than Just Physical Recovery

Spending nine months in a confined space takes a mental toll too. NASA’s regimen extends beyond physical therapy to include psychological support.

Astronauts often describe an emotional whiplash — going from the intense camaraderie of the ISS to the isolation of recovery. Williams and Wilmore will receive regular counseling to help manage this shift.

There’s also a cognitive aspect to consider. Studies show prolonged space travel can affect memory and concentration. NASA runs cognitive tests post-flight to track any decline and recommend brain-training exercises if needed.

Long-Term Health Monitoring: It Doesn’t Stop After Rehab

NASA’s care doesn’t end once Williams and Wilmore regain their strength. The agency tracks astronauts for years after their missions to study the long-term effects of space travel.

Some issues, like bone density loss, can persist for months or even years. There’s also growing concern about vision changes linked to increased pressure on the brain in microgravity. Williams and Wilmore will undergo regular eye exams to monitor any signs of trouble.

Data from their recovery will feed into NASA’s broader research — vital for future missions to Mars and beyond. Understanding how to keep astronauts healthy on long-duration flights is crucial to making those journeys possible.